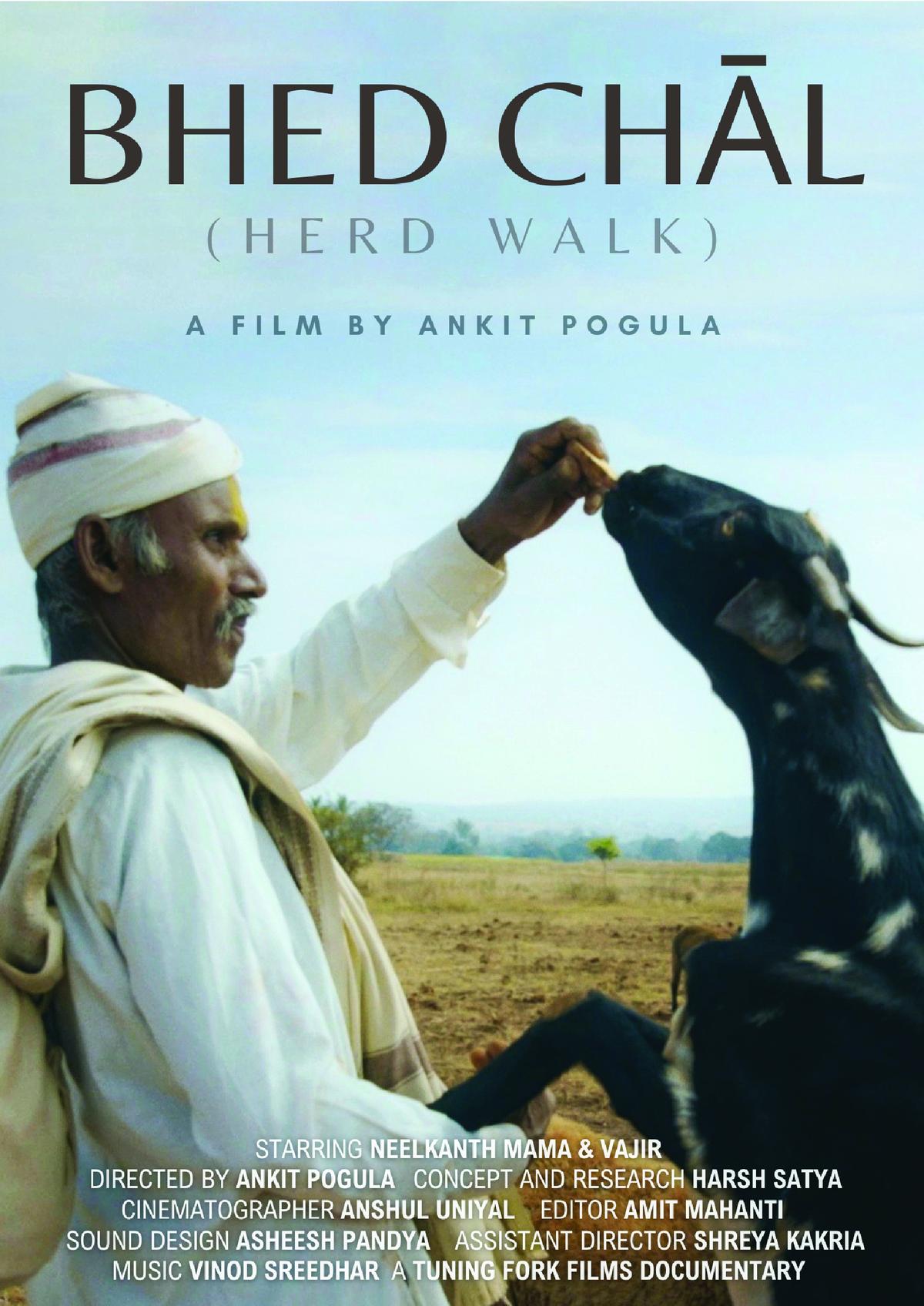

Herds of varicoloured Deccani sheep fan across the undulating Deccan landscape, seeking the odd patch of green amidst large swathes of rock-flecked sienna earth. Neelkant Kurbar, fondly known as Neelkant mama, dressed in white and wearing an ochre turban, picks his way through the rugged landscape as nimbly as the sheep, his firm, steady gait belying his 80-odd years.

Bhed Chal film poster.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL AARANGEMENT

For seven decades, he walked his sheep through this landscape until his son, Nagesh, died in an accident, and he had to give them away, we learn in the film Bhed Chal (Herd Walk), a documentary depicting the lives of the pastoral Kurubas of Karnataka. But it has not stopped this community elder from reminiscing about the old way of life. “I remember earlier times…this land was very good for increasing our herds…all open grasslands,” he says in the film, ruing how farmers have taken over these grasslands, using them for sorghum cultivation. “Land for animal’s grass, taken over for man’s bread.”

Works of Kuruba community displayed at the event.

| Photo Credit:

sreya

Bhed Chal was recently screened at Kurubkii, a three-day-long event showcasing the lives, livelihood and culture of the Kurubas, one of the oldest pastoralist communities in this region. According to the release, the event aims to highlight the often-overlooked voices of the Kurubas and foster a broader discourse of pastoralism in the Deccan region, helping us understand the ecological and social importance of this way of life.

Organised by Dakhni Diaries with the support of the Samagata Foundation, the event was all about celebrating this ancient community’s rich cultural traditions and practices. Some of the highlights of Kurubkii included a selection of kamblis, or traditional blankets, artworks and merchandise made of Dakhni wool, an installation depicting the stages of wool processing, photographs offering a glimpse into the daily life of the community and various events, including workshops, book launches, public talks and performances. “The event is more than a mere display,” states the release. “It is a platform to introduce young artists, designers, conservationists, and social workers to the Kuruba community’s craft, culture and conservational efforts.”

Pastoralism is believed to have emerged in multiple parts of the world between the Neolithic period, the final chapter of the broad prehistoric period we refer to as the Stone Age.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL AARANGEMENT

An ancient profession

Pastoralism, or the practice of rearing domesticated ungulates such as sheep, cattle, goats and camels on rangelands, is believed to have emerged in multiple parts of the world in the Neolithic period, the final chapter of the broad prehistoric period we refer to as the Stone Age. “Remember that pastoralism preceded agriculture; it has been around since at least seven to eight thousand BCE,” says the Kutch-based writer and social activist Sushma Iyengar, the lead curator of Living Lightly, a travelling exhibition focussing on pastoralism in the Deccan which will launch in Bangalore next February. “It is one of the oldest practices even in Indian culture,” she adds.

In the vast arid and semi-arid Deccan plateau, where monsoon variability is high, mobile pastoralism has always co-existed with rain-fed, subsistence farming and has been and continues to be a critical food provider, says Sushma. “This is the most resilient livelihood,” she says. Not surprisingly, many pastoral communities are still found in the Deccan, including the Gollas, the Kurubas, the Kurumas, the Rabaris, Dhangars and Banjaras, who display “ very seasonal and deductive movements in search of fodder and food and water.”

According to a publication titled Pastoral Communities and the Forest Rights Act, issued by the Centre for Pastoralism in 2021, pastoralism as a practice involves the seasonally mobile management of domesticated animals via extensive grazing on common pool resources, with at least 50% of household revenues coming from this kind of animal husbandry. “By this definition, pastoralism does not include intensively managed livestock (such as stall-fed dairies) or immobile households that manage a few animals that might be grazed on village commons, generating a small fraction of household revenues from their livestock,” states this report, pointing out that many of these pastoral communities are commonly associated with particular breeds of animals that they have played a vital role in developing.

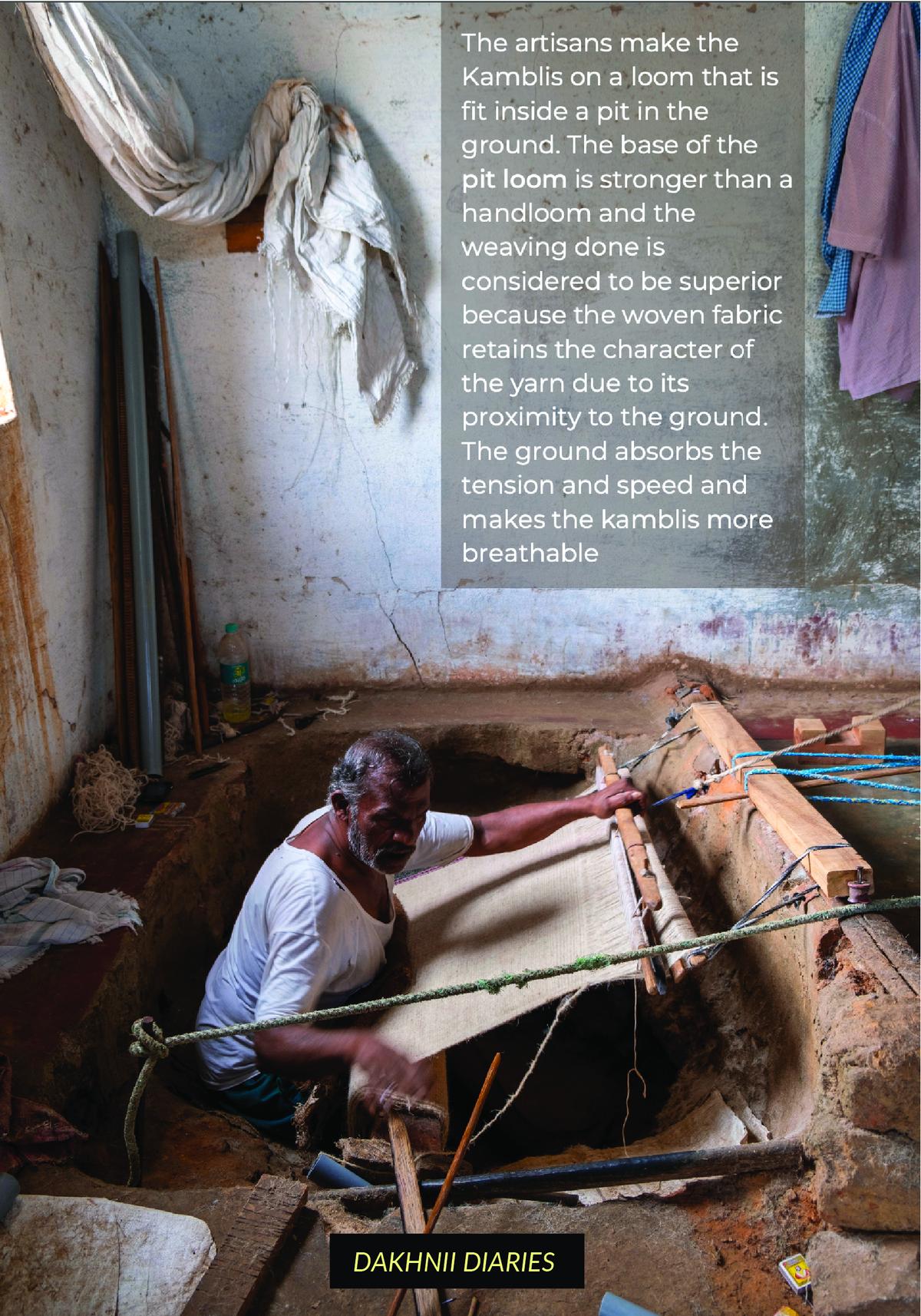

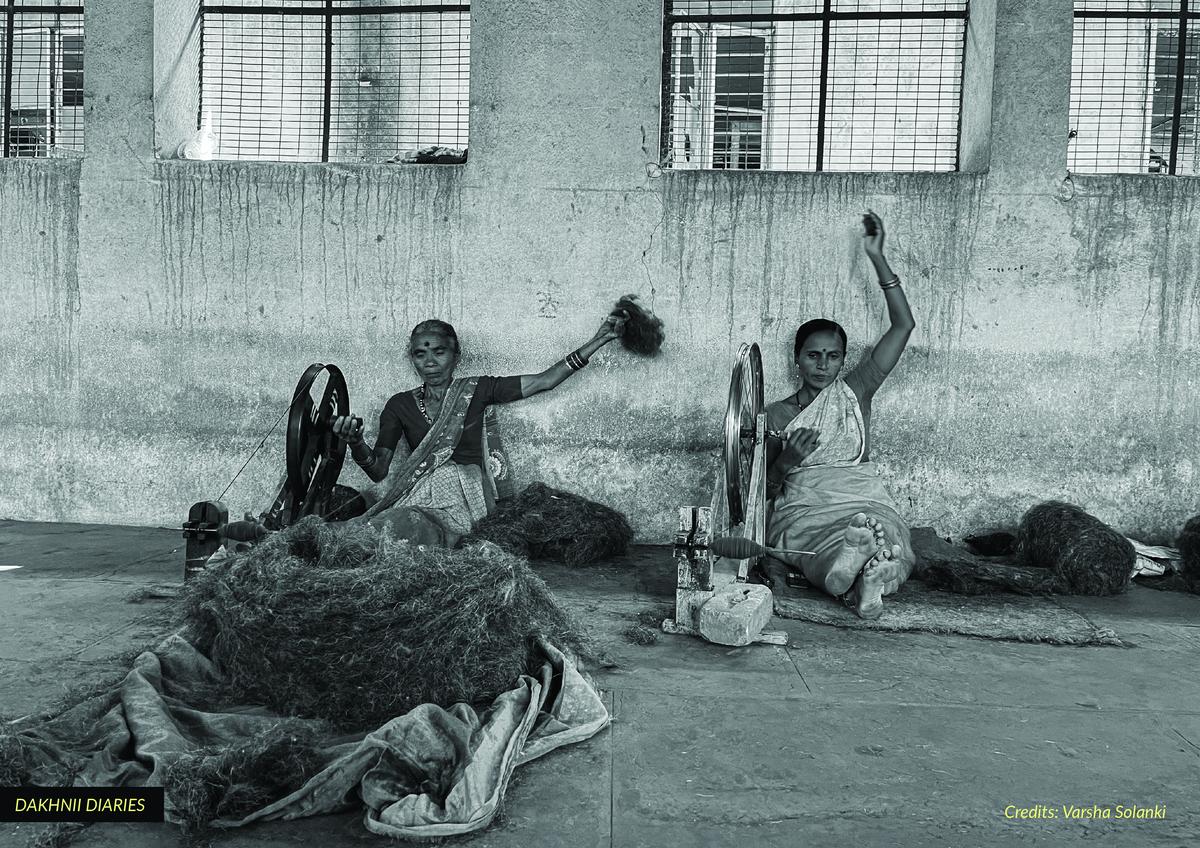

Traditionally, men from the community go out with the herds while women stay behind to make these kamblis, which once had a large market in India since they were sourced by the Indian Railways, police and military.

| Photo Credit:

Varsha Solanki

In the case of the Kurubas, it is the native Deccani breed of sheep, a hardy, medium-sized breed whose wool ranges in shade from ebony to ecru and has been used to make handwoven kamblis. “Ancestrally, we have been working with this wool to make kamblis, the entire process, carding, making yarn and weaving, taking place inside the house,” says Bharati Kaganikar, a Kuruba artisan from the Kadoli village in Belagavi district. Traditionally, men from the community go out with the herds while women stay behind to make these kamblis, which once had a large market in India since they were sourced by the Indian Railways, police and military. “However, the demand for them has come down,” she says. While they continue to make kamblis that are used for sacred ceremonies and by the community, they are also working with Dakhni Diaries to broaden their product range. “Now we make bags, mats, runners and drishti bands in between our MGNREGA work.”

Not only is this animal a source of wool, but it is also used for milk production, meat, and to produce organic manure, says Neelkant mama, who thinks of sheep-rearing as a sort of dharma. “This community is not doing this for money but sustenance,” he says. He launches into the origin myth of the community, which hints at an inextricable connection between the community and the animals it looks after. According to the legend, the Kurubas are the descendants of Padamgonda, one of six brothers, who, thanks to divine intervention, found sheep in an anthill and was told that he had to protect them. “If you take care of these animals, they will take care of you,” he says.

There are other challenges these communities face: complex issues around access to grazing on grasslands and forest ecosystems, lack of recognition by the state and limited access to essential services like healthcare and education.

| Photo Credit:

Varsha Solanki

A hard road ahead

For centuries, farming and pastoralism have forged a strong symbiotic relationship, with the pastoralists providing manure to the farmers for cultivation and getting food and money in return. “In arid parts of Karnataka, people still depend on animals for agriculture as they cannot afford to buy all the inputs from the market,” says Gopi Krishna of Dakhni Diaries, who has been working with the community for decades. Penning, or herding sheep into farmlands and leaving them there for a while to fertilise the soil, is crucial because it sustains agriculture and food security and makes sheep-rearing a viable profession for pastoralists. “He gets rice, tea, money, and other things when he goes for penning,” says Krishna, adding that this practice plays a huge role in sustaining a pastoralist lifestyle.

Neelkant mama, too, still remembers a time in the not-so-distant past when there was enough common land in the region to walk through, grazing his sheep en route. “Each village would be 100 km away, and the sheep would graze as we moved from village to village,” he says. “And we would give manure to the farmers at each of these villages.” Not anymore, however. As the population grows and more people have to be fed, much of the common land is now being used by farmers to grow crops. “Since you are using more and more land for rice and other food, the land available for the sheep is decreasing day-by-day,” rues Neelkant mama.

Not only is common land shrinking, but farming systems, too, have changed drastically. “The same farmers who would invite them for decades and centuries sometimes don’t want them now,” says Sushma, adding that there are other challenges these communities face: complex issues around access to grazing on grasslands and forest ecosystems, lack of recognition by the state and limited access to essential services like healthcare and education. “Things have changed, and they have become more aspirational…naturally want their children to study. But, as a society, we haven’t supported mobile communities such as pastoralists and encouraged mobile schools, for instance,” she says. “Women and children are increasingly choosing to stay behind while men move.”

Adapting to change

Pastoralists have traditionally always been adaptable, able to pivot when the need for it came up. “You know, climate change is not just today. It has been there in the past also,” he says Krishna, pointing out that the community has always been able to respond to biotic pressures. “Shortages and seasonality have always been there, but these people know how to make complex decisions in real-time.”

Something is working for them, agrees Sushma. “This is essentially the ability to adapt to the environment, the markets, the economic system,” she believes. For instance, as the demand for penning and locally produced wool has fallen — India imports most of its wool — they have turned to the meat market to sustain themselves. “The local wool market has dropped completely, but the meat market is very huge. Sheep and goat meat is a lucrative business, and the pastoralists have moved to that,” says Sushma.

This, in turn, means that production is changing to keep up with this new market: “more external food, vaccinations, chemicals, fodder…so the focus is no longer on the overall health of the sheep or the overall health of the culture or the ecology or the economy; it’s all productivity,” she says, explaining this shift has also caused many pastoralists to replace robust native sheep breeds with fatty cross-breeds. “They are compelled to respond to an overall system, policies and markets.”

Despite these challenges, Karnataka has been doing better than many others when it comes to their local pastoralist communities, she says. “Very few state governments have a compensation policy when calamities happen and animals get attacked by wildlife. Karnataka is perhaps the only state with this,” she says. The state also appears to be in favour of giving the community more forest rights. “There is apparently a move to create a more holistic grazing policy, which we look forward to, says Sushma.

Published – November 27, 2024 09:00 am IST